MESSAGE FOR THE WEBSITE, UPDATE FROM THE BOARD

Dear LIDERAMOS Friends,

As you may know, earlier this year we announced the selection of Angela Mictlanxochitl Anderson Guerrero, PHD, MPP, to serve as the inaugural Executive Director.

With over 25 years of experience in community engagement, policy, research, and guiding strategic change; as well as being a specialist in the effective communication of pluralities of knowledge across cultural and organizational borders, Dr. Anderson Guerrero brings a wealth of knowledge and skills to LIDERAMOS.

Now that the onboarding process has concluded, Angela’s has been hard at work communicating with funders, community leaders and other constituents. She’s also been working on forthcoming webinars, helping communities around the country who are interested in launching leadership programs, updating the organization’s website, and of course on the annual LIDERAMOS National Symposium, which is being held in San Antonio, at the Estancia del Norte – Tapestry Collection by Hilton, October 19th to 22nd. Lots going on for sure.

As the next phase of LIDERAMOS continues, the Board of Directors would like to publicly thank once again, Dr. Juana Bordas for her leadership, dedication and enormous commitment to the Latino community.

More importantly, for her vision in creating LIDERAMOS and leading it for five years! With LIDERAMOS, Dr. Bordas has left a legacy of leadership that will continue for decades to come as more and more communities across the United States implement Latino leadership programs using the model and curriculum created by Dr. Bordas and generously donated to LIDERAMOS.

Thank you for your support of LIDERAMOS and we look forward to seeing all of you in San Antonio at the Annual Symposium!

Warm Regards,

On behalf of the LIDERAMOS Board of Directors

Carlos F. Orta, Board Chair

Lideramos President, Juana Bordas, honored with Lifetime Achievement Award

“I am grateful for all the people who have supported me in bringing leadership practice to diverse communities and to help people understand that in a democracy, leadership is everybody’s business.” Said Juana Bordas upon learning that she will receive The International Leadership Association (ILA) Life-Long Achievement Award on October 26th in Ottawa, Canada. The award recognizes significant lifetime contributions including prominent published works, influential support of the body of leadership knowledge and practice.

“I am grateful for all the people who have supported me in bringing leadership practice to diverse communities and to help people understand that in a democracy, leadership is everybody’s business.” Said Juana Bordas upon learning that she will receive The International Leadership Association (ILA) Life-Long Achievement Award on October 26th in Ottawa, Canada. The award recognizes significant lifetime contributions including prominent published works, influential support of the body of leadership knowledge and practice.

Even Babies Discriminate…

(Excerpt: Article written by: Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman)

At the Children’s Research Lab at the University of Texas, a database is kept on thousands of families in the Austin area who have volunteered to be available for scholarly research. In 2006 Birgitte Vittrup recruited from the database about a hundred families, all of whom were Caucasian with a child 5 to 7 years old.

At the Children’s Research Lab at the University of Texas, a database is kept on thousands of families in the Austin area who have volunteered to be available for scholarly research. In 2006 Birgitte Vittrup recruited from the database about a hundred families, all of whom were Caucasian with a child 5 to 7 years old.

The goal of Vittrup’s study was to learn if typical children’s videos with multicultural storylines have any beneficial effect on children’s racial attitudes. Her first step was to give the children a Racial Attitude Measure, which asked such questions as:

How many White people are nice?

(Almost all) (A lot) (Some) (Not many) (None)

How many Black people are nice?

(Almost all) (A lot) (Some) (Not many) (None)

During the test, the descriptive adjective “nice” was replaced with more than 20 other adjectives, like “dishonest,” “pretty,” “curious,” and “snobby.”

Vittrup sent a third of the families home with multiculturally themed videos for a week, such as an episode of Sesame Street in which characters visit an African-American family’s home, and an episode of Little Bill, where the entire neighborhood comes together to clean the local park.

In truth, Vittrup didn’t expect that children’s racial attitudes would change very much just from watching these videos. Prior research had shown that multicultural curricula in schools have far less impact than we intend them to—largely because the implicit message “We’re all friends” is too vague for young children to understand that it refers to skin color.

Yet Vittrup figured explicit conversations with parents could change that. So a second group of families got the videos, and Vittrup told these parents to use them as the jumping-off point for a discussion about interracial friendship. She provided a checklist of points to make, echoing the shows’ themes. “I really believed it was going to work,” Vittrup recalls.

The last third were also given the checklist of topics, but no videos. These parents were to discuss racial equality on their own, every night for five nights.

At this point, something interesting happened. Five families in the last group abruptly quit the study. Two directly told Vittrup, “We don’t want to have these conversations with our child. We don’t want to point out skin color.”

Vittrup was taken aback—these families volunteered knowing full well it was a study of children’s racial attitudes. Yet once they were aware that the study required talking openly about race, they started dropping out.

It was no surprise that in a liberal city like Austin, every parent was a welcoming multiculturalist, embracing diversity. But according to Vittrup’s entry surveys, hardly any of these white parents had ever talked to their children directly about race. They might have asserted vague principles—like “Everybody’s equal” or “God made all of us” or “Under the skin, we’re all the same”—but they’d almost never called attention to racial differences.

They wanted their children to grow up colorblind. But Vittrup’s first test of the kids revealed they weren’t colorblind at all. Asked how many white people are mean, these children commonly answered, “Almost none.” Asked how many blacks are mean, many answered, “Some,” or “A lot.” Even kids who attended diverse schools answered the questions this way.

More disturbing, Vittrup also asked all the kids a very blunt question: “Do your parents like black people?” Fourteen percent said outright, “No, my parents don’t like black people”; 38 percent of the kids answered, “I don’t know.” In this supposed race-free vacuum being created by parents, kids were left to improvise their own conclusions—many of which would be abhorrent to their parents.

Vittrup hoped the families she’d instructed to talk about race would follow through. After watching the videos, the families returned to the Children’s Research Lab for retesting. To Vittrup’s complete surprise, the three groups of children were statistically the same—none, as a group, had budged very much in their racial attitudes. At first glance, the study was a failure.

Combing through the parents’ study diaries, Vittrup realized why. Diary after diary revealed that the parents barely mentioned the checklist items. Many just couldn’t talk about race, and they quickly reverted to the vague “Everybody’s equal” phrasing.

Of all those Vittrup told to talk openly about interracial friendship, only six families managed to actually do so. And, for all six, their children dramatically improved their racial attitudes in a single week. Talking about race was clearly key. Reflecting later about the study, Vittrup said, “A lot of parents came to me afterwards and admitted they just didn’t know what to say to their kids, and they didn’t want the wrong thing coming out of the mouth of their kids.”

We all want our children to be unintimidated by differences and have the social skills necessary for a diverse world. The question is, do we make it worse, or do we make it better, by calling attention to race?

The election of President Barack Obama marked the beginning of a new era in race relations in the United States—but it didn’t resolve the question as to what we should tell children about race. Many parents have explicitly pointed out Obama’s brown skin to their young children, to reinforce the message that anyone can rise to become a leader, and anyone—regardless of skin color—can be a friend, be loved, and be admired.

Others think it’s better to say nothing at all about the president’s race or ethnicity—because saying something about it unavoidably teaches a child a racial construct. They worry that even a positive statement (“It’s wonderful that a black person can be president”) still encourages a child to see divisions within society. For the early formative years, at least, they believe we should let children know a time when skin color does not matter.

What parents say depends heavily on their own race: a 2007 study in the Journal of Marriage and Family found that out of 17,000 families with kindergartners, nonwhite parents are about three times more likely to discuss race than white parents; 75 percent of the latter never, or almost never, talk about race.

In our new book, NurtureShock, we argue that many modern strategies for nurturing children are backfiring—because key twists in the science have been overlooked. Small corrections in our thinking today could alter the character of society long term, one future citizen at a time. The way white families introduce the concept of race to their children is a prime example.

For decades, it was assumed that children see race only when society points it out to them. However, child-development researchers have increasingly begun to question that presumption. They argue that children see racial differences as much as they see the difference between pink and blue—but we tell kids that “pink” means for girls and “blue” is for boys. “White” and “black” are mysteries we leave them to figure out on their own.

It takes remarkably little for children to develop in-group preferences. Vittrup’s mentor at the University of Texas, Rebecca Bigler, ran an experiment in three preschool classrooms, where 4- and 5-year-olds were lined up and given T shirts. Half the kids were randomly given blue T shirts, half red. The children wore the shirts for three weeks. During that time, the teachers never mentioned their colors and never grouped the kids by shirt color.

The kids didn’t segregate in their behavior. They played with each other freely at recess. But when asked which color team was better to belong to, or which team might win a race, they chose their own color. They believed they were smarter than the other color. “The Reds never showed hatred for Blues,” Bigler observed. “It was more like, ‘Blues are fine, but not as good as us.’ ” When Reds were asked how many Reds were nice, they’d answer, “All of us.” Asked how many Blues were nice, they’d answer, “Some.” Some of the Blues were mean, and some were dumb—but not the Reds.

Bigler’s experiment seems to show how children will use whatever you give them to create divisions—seeming to confirm that race becomes an issue only if we make it an issue. So why does Bigler think it’s important to talk to children about race as early as the age of 3?

Her reasoning is that kids are developmentally prone to in-group favoritism; they’re going to form these preferences on their own. Children naturally try to categorize everything, and the attribute they rely on is that which is the most clearly visible.

We might imagine we’re creating color-blind environments for children, but differences in skin color or hair or weight are like differences in gender—they’re plainly visible. Even if no teacher or parent mentions race, kids will use skin color on their own, the same way they use T-shirt colors. Bigler contends that children extend their shared appearances much further—believing that those who look similar to them enjoy the same things they do. Anything a child doesn’t like thus belongs to those who look the least similar to him. The spontaneous tendency to assume your group shares characteristics—such as niceness, or smarts—is called essentialism.

Peace, Reconciliation and Social Justice Leadership in the 21st Century

In Peace, Reconciliation and Social Justice Leadership in the 21st Century expert contributors explore the ways in which leaders and followers can bring forth pacifism, peace building, nonviolence, forgiveness and social cooperation. The chapters focus on the role of positive public policies on the national and international order, and the role leadership and followership plays in harmonizing differences and personifying space. They include lessons learned from post-conflict societies in Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chile, and others to remind us all that peace is a collective endeavor where no one can take a back seat. Bringing together leading scholars and practitioners from the worlds of leadership, followership, transitional justice, and international law, this research provides a blueprint of how people-led, bottom-up, grassroots efforts can foster reconciliation and a more peaceful world. Our 2019 Building Leadership Bridges book, published by Emerald, was edited by H. Eric Schockman, Vanessa Hernández, and Aldo Boitano.

In Peace, Reconciliation and Social Justice Leadership in the 21st Century expert contributors explore the ways in which leaders and followers can bring forth pacifism, peace building, nonviolence, forgiveness and social cooperation. The chapters focus on the role of positive public policies on the national and international order, and the role leadership and followership plays in harmonizing differences and personifying space. They include lessons learned from post-conflict societies in Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Chile, and others to remind us all that peace is a collective endeavor where no one can take a back seat. Bringing together leading scholars and practitioners from the worlds of leadership, followership, transitional justice, and international law, this research provides a blueprint of how people-led, bottom-up, grassroots efforts can foster reconciliation and a more peaceful world. Our 2019 Building Leadership Bridges book, published by Emerald, was edited by H. Eric Schockman, Vanessa Hernández, and Aldo Boitano.

Download a sample chapter from the Emerald website and purchase direct from ILA or your favorite bookstore.

Water Finds a Way – and We Should Too

By Dr. Kathleen Allen

In May of this year I spent some time on the North Shore of Lake Superior in Minnesota. We had a wet spring in this part of the country and lots of late snowfall in higher elevations. As a result, the high volume of water coming off the mountains and into the lakes and streams were the most dynamic I’ve seen in the 29 years I have been visiting. As I drove along the primary road that connects small towns along the shore, there were spontaneous waterfalls cascading down the rock faces bordering the road. It occurred to me that my timing was good. If I had visited later in the season the waterfalls would have dried up and I would have missed this amazing example of Nature’s power – and its capacity to adapt seamlessly from one form to another.

The experience got me thinking more about water – particularly the way it moves through the landscape. It reminded me that water always finds a way to flow toward gravity. The forms it takes continue to change and adapt based on the changing geography and the volume of water that is flowing. Pulled by gravity, water changes its form many times as it moves from the melting snow on the mountain tops toward the sea level. On the North Shore it moves seamlessly from trickles to streams, to falls, to rapids, to eddies, to backwaters, to slow moving currents, to filling Lake Superior. In fact, there are profound lessons in how water finds a way to move from one form to another that both humans and organizations can learn from.

Organizational Lessons from Water

There are two primary lessons we can take from the way in which water moves and adapts to its surroundings:

- Within organizations the power of purpose is synonymous with the power of gravity in nature. Water is constantly drawn toward the lowest level or sea level. Gravity shapes its direction and its adaptive capacity. Our version of organizational “gravity” would be a higher shared purpose. In other words, the purpose of the organization should shape the direction and adaptation of the organization. Without this clarity of purpose in the forefront of our thinking, human organizations tend to hang on to old forms and processes that hold us back from continually adapting and innovating as our external environment changes. Once an overall purpose is recognized it helps an organization let go of forms that no longer serve the organization.

- Adaptive cycles flow seamlessly from one form to another in nature AND in organizations. Water doesn’t stop to figure out if it is going to drop down a cliff and form a waterfall. It just finds the most efficient and effective way to move towards its purpose – gravity and sea level. Nature would never hold endless leadership meetings to analyze the “right” course of action and neither should we. As organizations, we can move toward our purpose much more efficiently by losing our rigid attachment to existing forms and beliefs, and instead work to guide the organization to its next natural form.

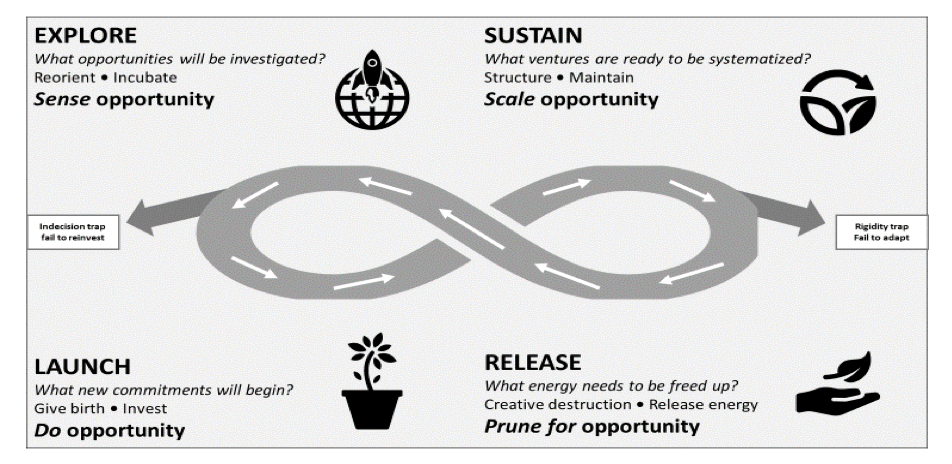

More about the Adaptive Cycle

The Adaptive Cycle shown below demonstrates how nature and 3.8 billion years of history have continually adapted. Just like water, the cycle continues in an infinite loop between explore, launch, sustain, and release to create an ongoing seamless flow. Nature is always moving and releasing one form to explore how a new form can serve its purpose.

This concept is a powerful lesson for human organizations and our leaders. We get into trouble when we fail to launch or when we fail to release. We need to see change as a constant flow, rather than merely moving us from one place to another. Without the right adaptive mindset, organizations lose the capacity to innovate – and lose ground to organizations who seek to continually adapt.

Water always finds a way to move from its starting point toward sea level. It doesn’t have consciousness or emotional reactions to changing geography that cause it to stop its adaptive cycle. Instead it continuously releases one form to launch another as it moves toward its true purpose.

If we could lead our organizations like water – and use our adaptive capacity in an infinite, water-like way – we would tap into a powerful ability to innovate and seamlessly adapt to a more natural, more successful way of being.

Dr. Kathleen E. Allen writes a blog on leadership and organizations that describes a new paradigm of leadership that is based on lessons from nature and living systems. She is the author of Leading from the Roots: Nature Inspired Leadership Lessons for Today’s World (2018) and President of Allen and Associates, a consulting firm that specializes in leadership, innovation, and organizational change. You can sign up for her blog on her website: www.kathleenallen.net

Dr. Kathleen E. Allen writes a blog on leadership and organizations that describes a new paradigm of leadership that is based on lessons from nature and living systems. She is the author of Leading from the Roots: Nature Inspired Leadership Lessons for Today’s World (2018) and President of Allen and Associates, a consulting firm that specializes in leadership, innovation, and organizational change. You can sign up for her blog on her website: www.kathleenallen.net

supports Lideramos

supports Lideramos